What explains our celluloid fascination with the Apocalypse? Is it like what Bill Bryson, in his famous book, ‘A Short History of Nearly Everything’, says, that except for a very few and fortunate species such as cockroaches, complete annihilation of the remaining flora and fauna is preordained? Or are we ‘enlightened’ enough to be able to foresee such an event and take adequate steps to minimize its effects or subvert it altogether?

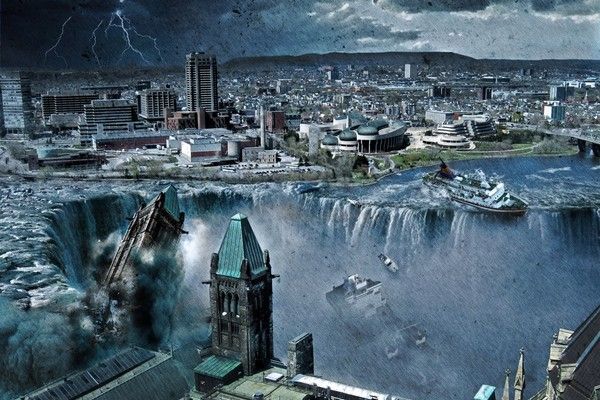

Apocalypse: Art by Steve McGhee

As visualized, there might be variegated forms of the apocalyptic future as we see or are yet to see it. From Stanley Kubrick’s celluloid adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, TerryGilliam’s 12 Monkeys, to Cuaron’s Children of Men, the future doesn’t seem to be bright – neither literally nor figuratively. Nonetheless, quite interesting is the fact that all these films appear to linger in a state of anarchy – somewhere between the Apocalypse itself, and the restoration of order. While this process unfolds, the characters are free to practice their free will. A few morbid examples as shown in such movies range from looting someone’s apartment at the point of a gun to murdering in cold blood. The social ethos seems to wither away as the proverbial Damocles’ sword is seen hanging above everyone’s state of existence.

Contrasting this phenomenon are societies such as the ones lucidly portrayed by George Orwell in his epic work ‘1984’, or for that matter, in movies such as Equilibrium, V For Vendetta, Minority Report etc. The grim picture of dystopian societies painted in these works of art is polarized in its concept from the ones mentioned previously, in those inhabitants of these ‘humanistic refuges’ are forced to live a robotic existence. All their actions are preconceived and synchronized, thus making them robots in a mechanical labor force. In this case, the humanness is suppressed to the extent of doing away with it altogether. However,how the protagonists redeem humanity from the clutches of despots ruling at the helm of such dystopias is a lot of climactic dramatization and a different matter altogether.

This brings us to the next question. Is an overseer, for instance, an elected government, indispensable to channel human morality in the right direction? Unfortunately, that indeed seems to be the case. We, as free-willed humans, are incapable of being watchmen of our own morality. Freedom, if unchecked, can wreak havoc. That is to say that unfettered freedom translates into unfettered presumptuousness; this seems to be the reason why rulers of the day have to do the tight-rope walk of choosing between freedom for their subjects or exposing them to constant surveillance. While movies do bring out this dichotomy beautifully, a cue that we can obtain from this inherent contradiction is the deepest nature of the human mind, giving way to the following words: It is said that art is a reflection of society, but the converse is also true, and this case, a formidable one.

What explains our celluloid fascination with the Apocalypse? Is it like what Bill Bryson, in his famous book, ‘A Short History of Nearly Everything’, says, that except for a very few and fortunate species such as cockroaches, complete annihilation of the remaining flora and fauna is preordained? Or are we ‘enlightened’ enough to be able to foresee such an event and take adequate steps to minimize its effects or subvert it altogether?

Apocalypse: Art by Steve McGhee

As visualized, there might be variegated forms of the apocalyptic future as we see or are yet to see it. From Stanley Kubrick’s celluloid adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, TerryGilliam’s 12 Monkeys, to Cuaron’s Children of Men, the future doesn’t seem to be bright – neither literally nor figuratively. Nonetheless, quite interesting is the fact that all these films appear to linger in a state of anarchy – somewhere between the Apocalypse itself, and the restoration of order. While this process unfolds, the characters are free to practice their free will. A few morbid examples as shown in such movies range from looting someone’s apartment at the point of a gun to murdering in cold blood. The social ethos seems to wither away as the proverbial Damocles’ sword is seen hanging above everyone’s state of existence.

Contrasting this phenomenon are societies such as the ones lucidly portrayed by George Orwell in his epic work ‘1984’, or for that matter, in movies such as Equilibrium, V For Vendetta, Minority Report etc. The grim picture of dystopian societies painted in these works of art is polarized in its concept from the ones mentioned previously, in those inhabitants of these ‘humanistic refuges’ are forced to live a robotic existence. All their actions are preconceived and synchronized, thus making them robots in a mechanical labor force. In this case, the humanness is suppressed to the extent of doing away with it altogether. However,how the protagonists redeem humanity from the clutches of despots ruling at the helm of such dystopias is a lot of climactic dramatization and a different matter altogether.

This brings us to the next question. Is an overseer, for instance, an elected government, indispensable to channel human morality in the right direction? Unfortunately, that indeed seems to be the case. We, as free-willed humans, are incapable of being watchmen of our own morality. Freedom, if unchecked, can wreak havoc. That is to say that unfettered freedom translates into unfettered presumptuousness; this seems to be the reason why rulers of the day have to do the tight-rope walk of choosing between freedom for their subjects or exposing them to constant surveillance. While movies do bring out this dichotomy beautifully, a cue that we can obtain from this inherent contradiction is the deepest nature of the human mind, giving way to the following words: It is said that art is a reflection of society, but the converse is also true, and this case, a formidable one.